To Efficiently Flatten Rough Lumber, Start with a Saw

In my last post I talked about the reasons that I think it’s important to learn to mill lumber by hand. The short version is that even though machines may make this work less physically demanding, the machines used in the vast majority of hobby shops have very limited capacities when it comes to the width of the boards that they can handle. However, hand planes have no such limits, so learning to dress lumber with hand planes keeps us from being limited by the capacities of our machines.

Today, I want to start to discuss the process of milling rough lumber by hand. It’s not a difficult process, but it is a process, and I find that following a specific set of steps helps to make the work easier and the results more consistent. I’ve been using and refining this process for 20 years, and while the way that I do it certainly isn’t the only way, it’s the method that I’ve found most efficient for me.

I’m also going to break the process that I use up into multiple posts. I’m not doing this because the process is difficult. On the contrary, it’s really quite quick and easy once you’ve done it a couple of times and understand the steps. However, it takes a lot of words and photos to thoroughly cover the steps and if I did it all in a single post, it would be a really long post. So just for the sake of brevity (at least brevity relative to how long winded I can be), I’m going to break the process up into multiple posts.

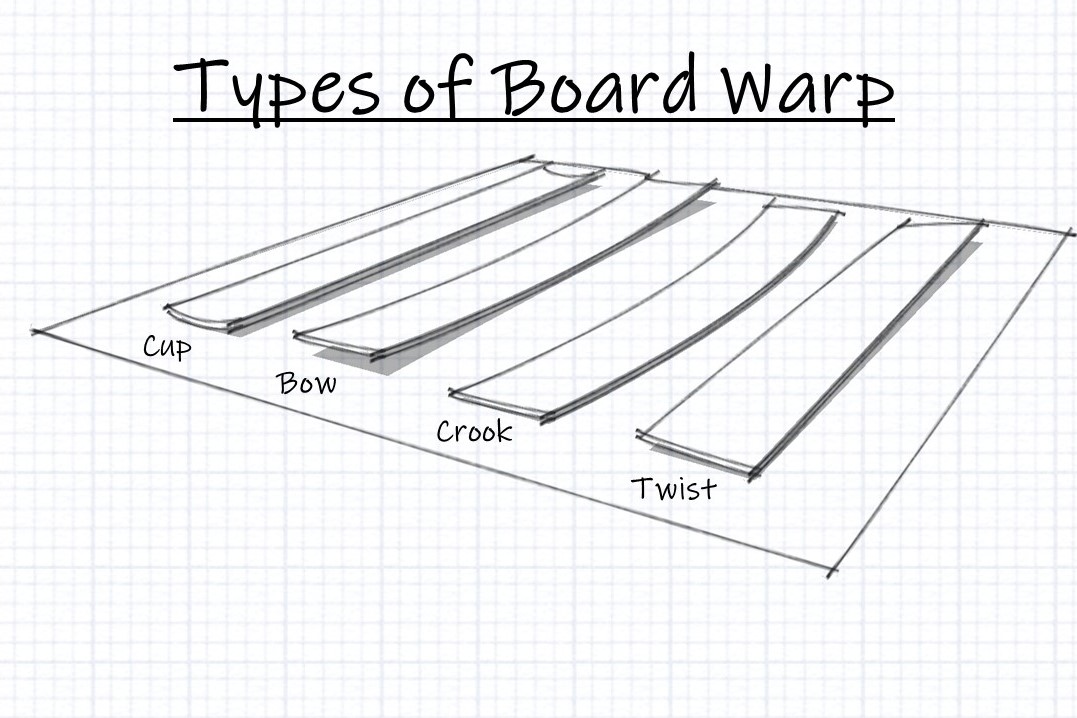

It’s important to understand that no matter how straight a tree grew, or how well it was sawn and dried, every single board is going to have some degree of warp – cup, bow, crook, and/or twist (a.k.a. wind). So before ever picking up a hand plane, the first step in the process that I use to mill rough lumber is to assess the current condition of the board. I want to know the degree of warp in the board and determine the best strategy to reduce the impact of that warp before I start planing.

It’s a very rare case when there will be a need to plane the entire board as is. When making a long length of molding, we might need to plane the entire length of a board, but we wouldn’t need the full width. If the board will be used for a wide door panel or case side, we might need to plane the entire width of the board, but not the full length. So, in almost every case, it’s beneficial to cut boards into smaller, more manageable parts before processing them with hand planes. I typically cut my rough sawn boards about 1″ oversized in length and about ½” oversized in width before I plane them.

Using a saw is typically a much faster way to deal with warp than using a plane. By making some strategic cuts, we can minimize the amount of warp that remains in the oversized parts, which minimizes the amount of planing necessary to make the boards flat, square, and ready for joinery. Using the saw first can also help preserve the maximum amount of thickness.

Let’s look at a few examples.

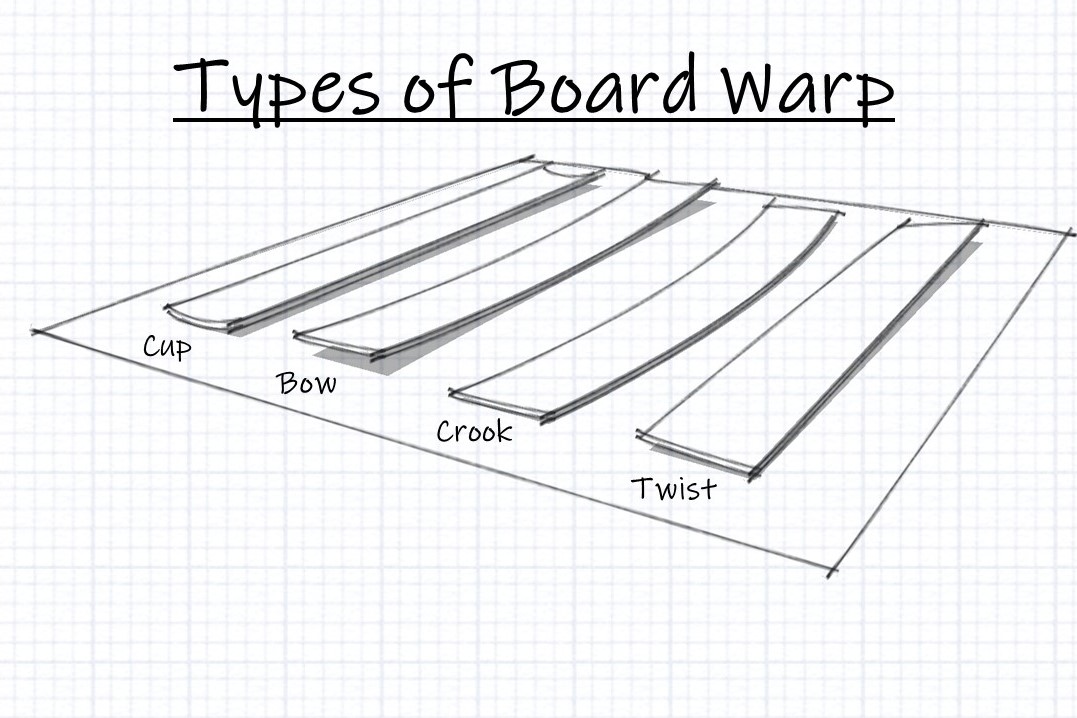

In the above photo, the full width 1″ thick board on the left has a pretty significant cup across its width. If this board were planed to remove the cupping, the maximum thickness that could be gotten out of the board would be about 1/4″. However, by ripping the board into three narrower boards, the impact of the cupping is drastically reduced and only about 1/16″ of material would need to be planed to make the board flat, leaving a board of about 15/16″ thick.

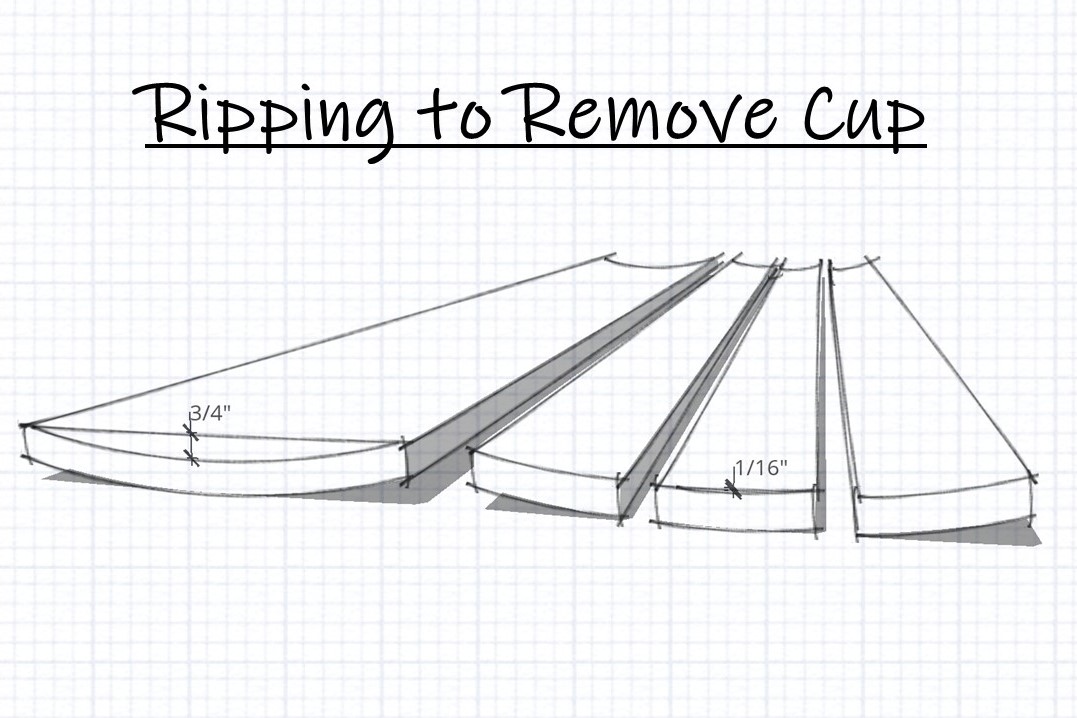

What about bow? In this case the impact of the bow can be reduced by crosscutting the board into shorter lengths. The example above results in a bow of 2″ from end to end being reduced to only 1/4″ when the 8′ board is crosscut into three shorter boards. A bow of 2″ is, of course, quite exaggerated from what we would normally observe, but it does demonstrate the significance that cutting the board can have on reducing the impact of the bow.

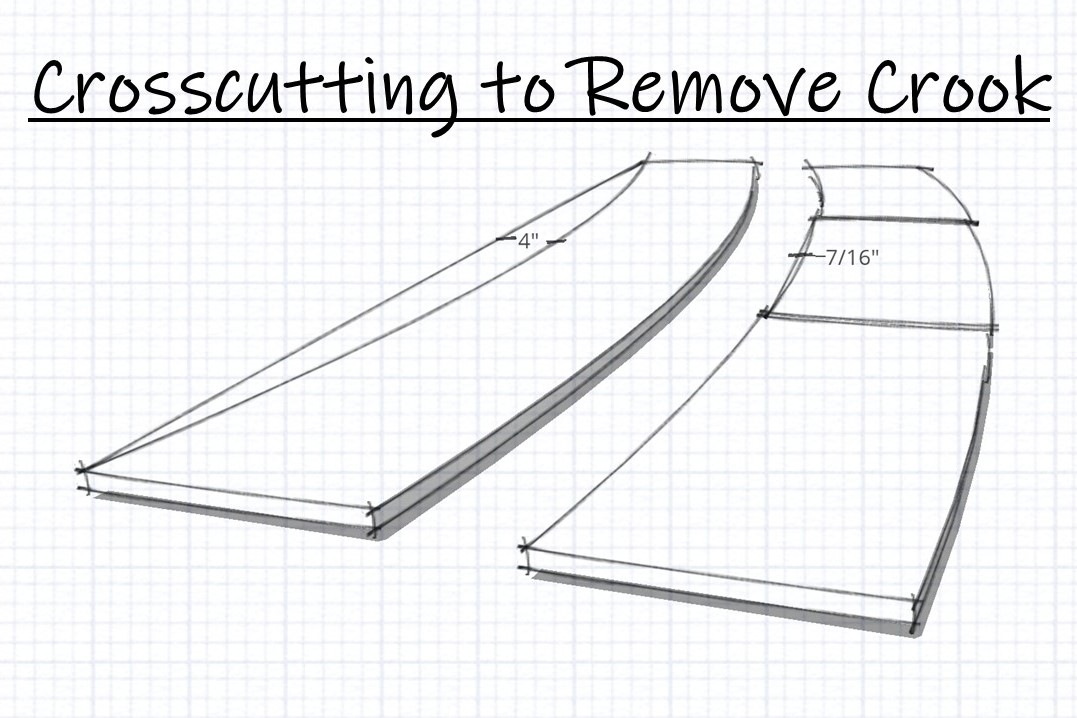

Crook works similarly to bow, but there is an option to rip or crosscut. By ripping the crook can be removed at the expense of some board width. This may not matter if the width of the board is not critical. However, if the board is crosscut first, then much less width will need to be removed from the board in order to straighten the edge.

As for twist, both ripping and crosscutting will work to remove some of the warping. In my experience, however, crosscutting twisted boards tends to preserve more of the board’s thickness than ripping does. Twist, or wind, in boards is often the result of internal tension due to the way the tree grew, not a result of the sawing and drying process. Often times, when a twisted board is ripped narrower, some of that tension is released and the board twists even more. If long boards are necessary, I’d suggest avoiding boards with any significant twist.

So, now that we’ve strategically broken our boards down into slightly over sized parts, and reduced the effect of warping as much as possible, we’re ready to start planing.

4 Comments

With home center 1x or 2x lumber, would you expect that to warp if taken from a home-center covered-external wood yard and placed in an unheated garage for 1-2 months? I ask as home center lumber is often damp to the touch, so my suspicion is that it is not well dried. Thanks

Hi John,

It depends on the species, grade, and what it is being sold for. I’ve found that the Radiata pine, poplar, oak and maple that I’ve gotten from the home center tends to be pretty good and stay pretty flat IF it’s flat when you get it. The white pine/yellow pine/spf 1X material is also pretty good, again, IF it’s flat when you get it. The 1X material is frequently already warped in the rack at the store. But if you’re picky, you can find usable stuff, and it’s usually pretty stable. The framing lumber (2X stock) is almost always not dry enough for woodworking when you get it. So I’d let that stuff dry for several weeks to several months before working with it.

We’re a lot more limited in wood selection in Home Depot/Rona/Lowes here in Canada than you are in the US. Only SPF is commonly available and virtually no 1x (the lack of 1x I suspect is the saw mills focusing on 2x during Coronavirus). I pick the flattest ones, often from lower down the pile. I picked a bunch of 1x this past weekend, minimal warp when i picked them, so I’ll see how they do over the next month. Thanks Bob.

Thank you very much for all your work mate!